Suffragist Helga Estby and her daughter, Clara, set off on an amazing journey in 1896, walking across the United States, but what should have been an inspiring tale ended in heartbreak.

Helga was born in Norway 1860, and her hardship in life started early. Her father died when she was only two years old. Her mother remarried, but it was a time of economic turmoil and her stepfather had to leave the family to find work. He emigrated to the United states, sending for his family once he had found a stable home and employment for them. Helga was only 11 when she arrived in her new homeland, but she adapted quickly. She seems to have done well in school and became fluent in English.

Five years later, Helga faced a crisis when she became pregnant. In this era, being an unwed mother was a terrifying and shameful situation. It must have been very difficult for her to admit her pregnancy to her family. The father of Helga’s child is nowhere mentioned in the historical records, but it can be assumed he either refused - or was unable - to marry Helga and make an “honest woman” of her.

Her family arranged a marriage with a man named Ole Estby and the baby, Clara, was born a month after the wedding. Ole took his bride and baby daughter out west to a homestead claim. They made their home in a prairie sod cabin. Clara probably learned to crawl on its dirt floor. It was a hard life, but they managed to make it work. Helga had three more children, Ole - named for his father - Olaf, and Ida. Young Ole died as an infant, as so many children of that era did.

Adding to this grief were terrible trials such as wildfires which swept the area, fierce storms, and epidemics of disease. Ole finally had enough and packed up his family to move west again. As far as west goes, in their case, moving all the way to Spokane Falls, Washington. More children came along in due time.

The family’s fortunes seemed to be improving. They bought lots in the thriving little town and Ole quickly found carpenter work. But then Helga fell on a dark night on the unlit streets. She was severely injured and had to have pelvic surgery, a severe blow to the family’s finances.

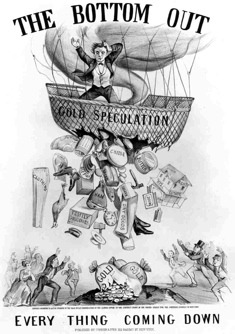

In 1893, an economic depression hit the country hard. Banks in those days had very little regulation or oversight. Panics - financial collapses caused by unstable financial institutions - were frequent. But this one was particularly bad, caused by speculation on gold and the railroad-building bubble. Bank runs by people panicked their deposits would vanish if their local banks folded caused a ripple effect that spread across the nation. Unemployment skyrocketed.

And then Ole himself was hurt, a debilitating injury that left him unable to work as a carpenter - not that there was much work to be had during the time. Helga later wrote an account of that dark time period:

For eight years we have had misfortunes. It was eight years ago that I fell one night over an obstacle in the streets of Spokane and was so badly injured that it made me sick for two years. Then I had an operation which laid me up a while and then cured me. About seven years ago my husband fell and fractured his knee cap. Afterward a horse fell on him and completely laid him up. Five years ago my daughter Ida went blind. She was treated in a hospital and is about well. Then my eldest boy got inflammatory rheumatism. Two years ago our house burned down, and as we had no insurance on it we only built up the kitchen part of it.

The family borrowed against their property to try to survive, but that short-term survival technique put their future in jeopardy. By 1896, Helga’s family was on the brink of ruin. They were facing foreclosure.

Helga learned of a sponsor in New York willing to pay $10,000 if a woman would walk across America. The details of the deal are sketchy - today, it’s unknown who it was who made the wager, or how Helga learned of it. She corresponded with the sponsor and a contract was drawn up. Helga had seven months to complete the task. Allowances would be made in the schedule for illness that occurred along the way.

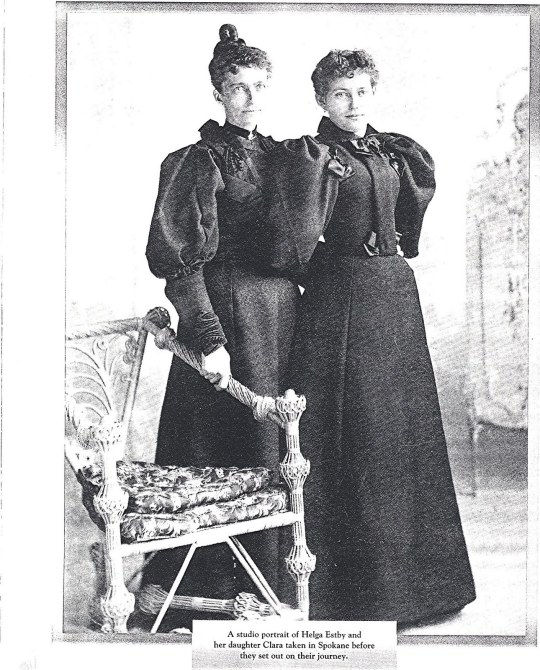

Helga was a strong woman and a supporter of the suffragist movement. She believed if she managed to accomplish the task, it would bring public awareness of the fact that women could do anything a man could do. She reassured her family somewhat in that she would not travel alone - she would take her eldest daughter, Clara, along on the trip. She secured an official letter of introduction from Spokane’s mayor, which would serve her credentials.

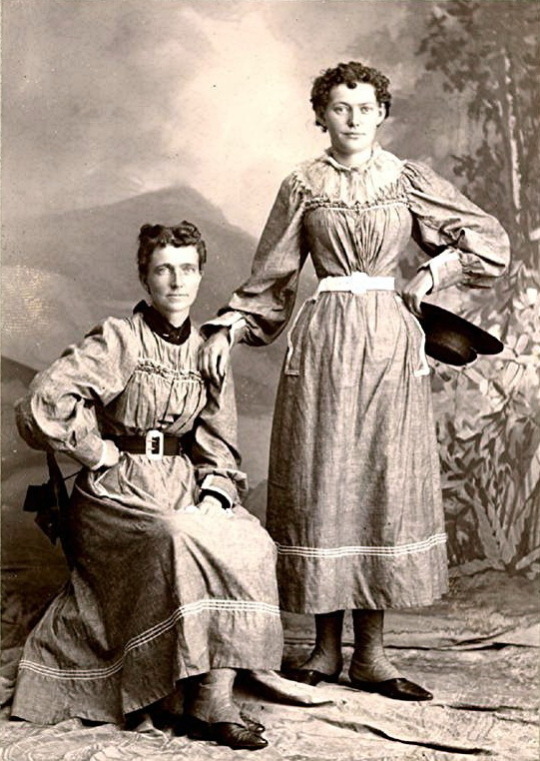

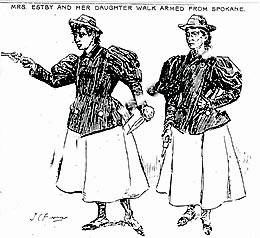

After getting some photos of herself and her daughter printed up, she also had made some calling cards - those essential pieces of Victorian ladies’ paraphernalia - that read, “H. Estby and daughter. Pedestrians, Spokane to New York.” She hoped to sell the photos along the way to supplement their funds. They took no luggage with them, only a small satchel that contained a gun, a curling iron, a knife, a container of pepper spray, and a notebook so Helga could keep a journal of their travels. They had only five dollars cash, probably all the family could spare. The newspaper account announcing their journey hastened to add that they were respectable women, but would “rough it” like tramps for their trip.

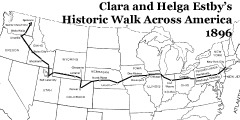

It wasn’t an easy journey, by any means. Following the railroad tracks, Helga and Clara made their way east, stopping in towns along the way. There, they would first find the local newspaper reporter to give an account of their journey thus far. They would try to find temporary employment to feed themselves and sleep indoors, sewing, cooking and cleaning for their room and board. They did not ask for charity, but would gratefully accept lodging for the night if offered. On the whole journey, they only had to spend nine nights outdoors.

The articles about them continued to stress their respectability despite their unladylike travels. One article noted that Clara never drank anything other than milk and Helga only allowed herself one cup of coffee per day. Almost every article noted that Helga was an immigrant, and complimented her command of the English language.

Along the way, they had to purchase new shoes and new clothing. They wore through 16 pairs of shoes apiece. At one point, the women abandoned the long dresses they had worn and adopted the new “bicycling costume” that women were wearing while riding bikes. It was more comfortable and more suitable for hiking, though it was not proper to be worn in any other context. (In other words, it was improper to wear it walking around a city or dining… Much like it would be today if someone were wearing a bathing suit to a restaurant.)

Helga and Clara were flouting convention in many ways, but Helga’s charm seems to have convinced newspaper editors who met her to present her in a positive light.

They once nearly drowned in a flash flood and escaped a brush with a hungry cougar. At one point, Helga was attacked by a homeless man and ended up shooting him in the leg to escape. Helga also said they’d once been accosted by a group of Native Americans, who rifled through their pack and were fascinated by Clara’s curling iron. They were probably wondering why the women would lug such a thing around on a cross-country journey when they hadn’t even brought a change of clothing.

But despite the hardships, they made across the country. On the last leg of their journey, Helga sprained her ankle. They wrote to the sponsor, asking for a an extension on order to give her time to heal.

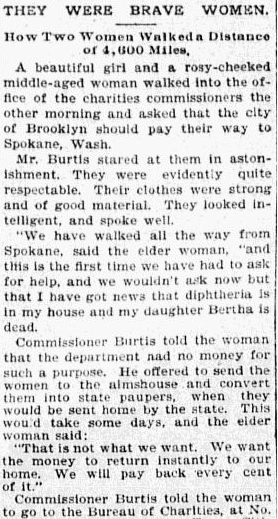

They arrived in New York City the day before Christmas Eve, 1896, a little more than two weeks late, triumphant and exhausted. But to their shock, the sponsor refused to pay their $10,000 reward, citing the fact they were over their deadline. The contract had allowed for delays due to sickness, not for injury. The sponsor refused to even pay for Helga and Clara return trip home.

They were stranded in New York for the winter. Helga found a publisher willing to pay her the money if she wrote a book about her experiences, but the journals she had carefully kept along the way were stolen or lost while they were in New York.

While they were there, Helga got the first letters from her family she had received in seven months. They contained the tragic news that her family had been stricken with diphtheria. One son was hospitalized and one daughter was dead.

Finally, Helga reached out to a railroad owner, who took pity on their tragic tale and gave the women two tickets to ride his rail line as far as Minneapolis. The rest of their journey is lost to history, but they likely took a train the rest of the way back to Spokane.

Without the promised reward, their property was foreclosed. Helga’s neighbors shunned her for “abandoning” her family for that crazy adventure. She had set out to prove that women could do anything, but in her neighbor’s minds, there were some things women should not do, and that included ladies leaving their home to go on an unchaperoned (and publicized!) journey across the US, leaving their children to suffer in their absence.

Helga’s family eventually recovered from their financial hardships. Clara went off to college and became a successful businesswoman. Ole and one of his sons started a construction business, and the family settled into quiet prosperity. But more than one account says the family harbored resentment against Helga for her “abandonment” of them.

Helga remained active in the suffragist movement, likely not endearing herself further to her neighbors. But she saw the triumph of the movement when women achieved the vote in Washington State in 1910.

Starting in about 1920 Helga tried writing a book about her amazing journey, piecing the tale together bit by bit and using newspaper clippings to supplement her memories. She never finished it before her death in 1942. She had entrusted the memory of her story to one of her granddaughters, but the girl was unable to save her grandmother’s manuscripts and numerous newspaper clippings. One her family members gathered up the manuscript and burned it after her funeral, though the girl managed to snatch two clippings from the barrel before they burned. That was a common practice in the Victorian era, meant to protect the privacy of the dead.

In the past few years, several books have been published about Helga and Clara’s amazing journey, and her courage is finally being recognized.

Sad they burned all her history

ReplyDelete